Hits: 227

This week the Public Health Emergency (PHE) for COVID-19 is ending in the U.S. This means many things, but one major shift will be the data—the dashboards and updates we’ve grown accustomed to.

Why the change?

The public health system in the U.S. is complicated. But, essentially it’s decentralized. In other words, the federal government (i.e., CDC or HHS) is not the “center” of the public health universe. Public health is local. What “local” means depends on the state—driven by state health departments (like in Vermont) or by counties within a State (like in Texas).

On one hand, this decentralized system is a good thing. Flexibility allows health departments to focus on problems relevant to their population in their specific context. The approach to a public health problem in Texas, for example, is different from in Vermont. This also means health departments have full autonomy to decide how data is collected, what data is collected, and what is communicated.

During a national emergency, this decentralized system became a massive problem, though. It was impossible to get a national picture of what the hell was going on in a timely, comprehensive, and consistent manner: who’s at risk, how is the virus changing, and how are vaccines working?

Slowly the PHE stepped in: mandate health departments to feed data to the CDC. This meant that COVID-19 data (eventually) traveled from county → state→ CDC→ national dashboards.

As you can imagine, there were a lot of places where this flow broke down:

- CDC had to literally create and sign data use agreements (i.e. contracts) with every county- or state-level entity for certain data.

- The majority of health departments didn’t have the resources, manpower, infrastructure, or technical knowledge to collect or report data due to complexity. Some counties were sending case reports via fax.

- There was a problem with data consistency within and between states. Is El Paso collecting, measuring, and reporting the same data as Massachusetts? In short, no.

- Then there were politics. Even if health departments had the data, some states didn’t report it.

Over time, most problems were smoothed out.

But it took an incredible amount of time, resources, coordination, and manpower to get where we are today.

The PHE ending means that data flow, from county → nation, is no longer required. But this doesn’t mean that everything is disappearing:

- Health departments may still update locally;

- Some health departments are still willing to report data to CDC, even if not required;

- The CDC has sentinel surveillance programs— a set of locations chosen for intensive surveillance. This will allow us to see trends but not counts.

What is changing?

No change:

- Wastewater and genomic surveillance, which will allow us to track variants and transmission.

- Emergency room data, which is one of the best early indicators of state-level transmission.

Changing a little:

- Hospitalization data will remain through April 2024, but frequency of reporting will change. This will help us track severe disease.

- Death data will remain, but the data source is changing.

Changing a lot:

- Test positivity rates —one of our earliest metrics of transmission—will no longer be national, state, or county-wide. Negative tests no longer have to be reported. But, some pharmacies will still report.

- Cases will be dropped. This makes sense given at-home antigen tests.

- Vaccination coverage will be spotty. The frequency of updates will also change.

What to do on an individual level?

The CDC transmission levels data is going away. Starting today, the CDC recommends using hospitalization data to guide behavior. If numbers go up, put on a mask.

I don’t really agree with this for several reasons. I suggest following wastewater trends either locally or regionally. (If it’s going up, put on a mask.)

What to do on a national level?

Moving forward, the key is to prepare so this data problem doesn’t happen again during an emergency or every winter. We do that by changing how we fund, plan, and coordinate our public health system.

The CDC is giving states money to modernize their data infrastructure (move away from faxes, for example). This may sound simple, but it is incredibly complex, technical, and expensive. Unfortunately, there are already a few bumps:

- Funding is going to the states, leaving some local health departments with no money to modernize.

- Little to no coordination. Even if states or local health departments are modernizing, they are doing so using their own priorities and with no guidance.

Bottom line

On Thursday there will be a shift in data. We won’t be flying blind but it’s not the best we can do. We need to figure out how to sustain our top notch work when we are not in an emergency.

Love, YLE

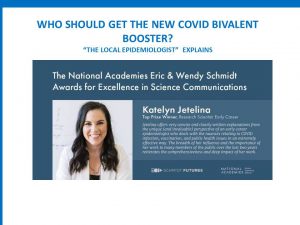

“Your Local Epidemiologist (YLE)” is written by Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, MPH Ph.D.—an epidemiologist, data scientist, wife. During the day she works at a nonpartisan health policy think tank and is a senior scientific consultant to a number of organizations, including the CDC. At night she writes this newsletter. Her main goal is to “translate” the ever-evolving public health science so that people will be well-equipped to make evidence-based decisions. This newsletter is free thanks to the generous support of fellow YLE community members. To support this effort, subscribe below.